What Is Time?

One way to wrap your mind around something this vast and mysterious is to think of time as a dimension, like space.

Scientists have many more questions than answers, but there is some agreement about time’s direction and relation with space.

©iStockphoto.com/stanislave

Unraveling the Mystery

It’s not easy to step back and think about how time works. Our experience of it distorts our sense of time passing: Vacations can feel like they fly by in an instant, and being stuck in traffic might seem like an eternity.

Scientists struggle to get a grip on the subject too. They have many more questions than answers. Does time have a beginning or an end? What happened before the big bang? Will we be able to time travel some day?

At the moment, there are only two things that physicists agree on: Time has just one direction, and space and time together form an entity called spacetime.

Space + Time = Spacetime

“Time is a dimension, just like space, that we exist in. But the difference to space is that we can’t step right and left, we can only go in one direction,” said Professor Astrid Eichorn of the University of Southern Denmark in a recent interview with timeanddate.

“And this is why we perceive time very differently from space.”

Physicists combine space and time and describe the universe in terms of spacetime. “One of the interesting things we learned in the 20th century about time and space is that they are not fixed and sitting in the background,” adds Professor Eichhorn.

“Anything that has energy or mass curves spacetime. What that means is that time stretches or contracts depending on whether we are close to something very massive or far away.”

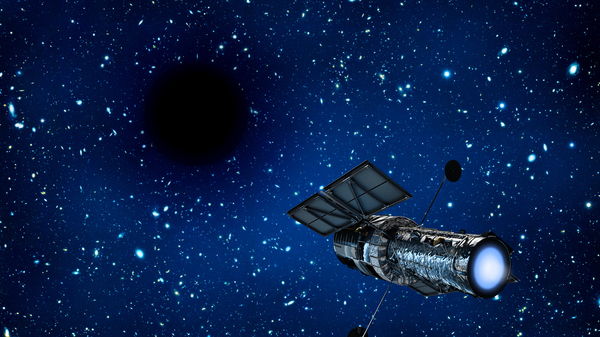

Would a spacecraft hovering near a black hole be able to travel to the future?

©iStockphoto.com/scaliger

Temporal Bending and the Dream of Time Portals

In the world of entertainment, there’s a seemingly infinite supply of stories that include time travel.

A lot of fiction about crossing time boundaries imagines using black holes as doorways to the past or future. Created when dying stars implode, these objects are so massive that space, matter, and even time bend near them.

This temporal bending means time passes more slowly near a black hole than it does further away, so some writers have imagined there might be ways to take advantage of this difference and create a form of time travel, but that is pure speculation at this point.

A Shortcut to the Future?

What about wormholes? The idea of using hypothetical tunnels in the fabric of spacetime to create shortcuts has been another favorite of science fiction.

But there are thorny scientific problems to solve to make this idea viable. First, to create a wormhole, we would likely need something with negative energy, which may or may not be possible.

In practice, time travel would probably have to involve an element of space travel, too. The Earth, solar system, and Milky Way galaxy are constantly in motion. If this movement wasn’t accounted for, a time traveler emerging from a wormhole might find themselves in empty space, a long way from anywhere.

We can think about time on a huge scale to understand slow processes like erosion, or to measure incredibly small intervals like zeptoseconds.

©iStockphoto.com/Freethedust

From Deep Time to Zeptoseconds

Our understanding of time also has a lot to do with the scale of our inquiry.

When we think of huge numbers like the age of the Earth, which is currently thought to be about 4.5 billion years, scientists use a concept known as Deep Time, which was introduced by John McPhee in the early 1980’s.

This idea examines the enormous changes that happen gradually over the Earth’s lifespan—events that take place over billions of years.

Charles Darwin, drawing from some of the work of Charles Lyell, drew on an understanding of the cumulative effects of billions of years of processes to help develop his theory of evolution.

But we can think of time as happening in the tiniest of fractions of a second, too.

Science has recently managed to measure the shortest interval so far—the amount of time it takes a light particle to zip across a molecule of hydrogen. This has been clocked as 247 zeptoseconds, which are a trillionth of a billionth of a second. (You can imagine it as a number which is a decimal point followed by 20 zeros and a 1.)

Keeping Track

Humans have developed tools for keeping track of time, from the crudest stone sundials and calendars to today’s atomic clocks that are precise to the microsecond. Ironically, no matter how we measure it, or think about the vastness of time, it can feel like there’s never enough of it in our hectic lives.

As far back as 5000 years ago, Babylonians and Egyptians began introducing calendars as a tool to track time, help organize events, make trade easier, and keep the cycles of agriculture on track.

How the Babylonians shaped our 7-day week

Through the years, we’ve become much more precise in our timekeeping. Today’s standard for precision are atomic clocks that measure the vibration of atoms via a quartz crystal oscillator. And they are incredibly accurate: Some are calculated to be off by only 1 second over the course of the next 100 million years.

Earth: The Planet as a Timer

But few people realize our home planet itself is also an accurate timekeeping device. In fact, Earth is one of the most reliable clocks known, with a startlingly precise rate of spin every day. As a result, our 24-hour day holds steady at a timing of very close to 86,400 seconds, with only tiny amounts of variation.